People were created to be loved. Things were created to be used.

The reason why the world is in chaos is because things are being loved and

people are being used.

---Unknown

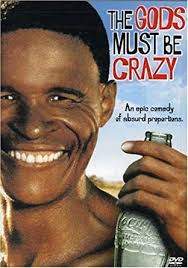

What would have happened had our ancestors not chosen to progress

forward and make life easier? Would we be more carefree, like the Bushmen in

Jamie Uys’ 1980 film, The Gods Must Be Crazy? Unfortunately, there is no

empirical way to answer the question. However, what can be answered is how the

decision to progress forward has shaped the society that we have come to

know. Our lives are very similar to the urbanites in Uys’ movie. While we have

been walking the path of progress, fitting ourselves into a daily schedule and

a select set of social norms, we have forgotten one of the most important

things in life: happiness. Unlike the Bushmen, it is rare for a member

of our society to feel joyous well-being. Should it happen to someone, that

individual is often judged as selfish, their felicity in question. If the only

thing we care about is conformity and keeping busy, we may lose sight of the

gifts that contentedness and love can bring.

Uys expands on the difference between the Bushmen and Western society

by depicting Kate Thompson following the same exact routine every. As the

voice-over reminds us, Western society expects its citizens to “adapt and

readapt himself to every day and every hour of the day to his self-created

environment” (Uys 06:25). Because humankind chose to force their natural

surroundings to adapt to their own needs, they now have to readapt their lives

to fit into what they have made. Life consists of waking up, going to

work or school, going back home, eating dinner, doing homework, and then going

to sleep, with some other activities and chores plugged in here and there every

now and then. This type of a life is the typical day-to-day circumstances that

just about every person leads. It is how Kate Thompson lives, given that she has

a conventional job as a journalist. The problem is that these individuals are

not necessarily enjoying their quality of life, at least not like the Bushmen.

In the Kalahari Desert, the Bushmen have adapted their lives to

nature, as opposed to making nature adapt to their lives like Western

civilization. The Bushmen rely on the resources found within the natural

surroundings around them for survival. Competition does not exist; there is no

sense of ownership and no bitterness. As the narrator puts it, “they must be

the most contented people in the world” (Uys 02:46). They feel blessed for

everything they have, and believe that the gods have given them everything they

will ever need. Their lives are peaceful. That is, however, until Xi finds an

empty Coca-Cola bottle that “fell out” of the sky.

Because of their strong belief that the gods send them essential

needs, the Bushmen take the Coke bottle as a gift. They, then, learn how to use

it for many different tasks and adapt it into their everyday lives; it becomes

a snake skin smoother, a pounder for food, “ a musical instrument, a

patternmaker, a fire starter, a cooking utensil, and, most of all, an object of

bitter controversy” (Ebert, par. 2). Despite never having felt anger, hatred,

or jealousy before, the Coke bottle invokes these exact emotions.

Tension builds, anger arises, the feeling of ownership develops, and, worst of

all, violence breaks out. After the tribe realizes how the bottle has changed

them, they unanimously decide that it is best to get rid of the so-called

“evil” bottle. So, Xi takes a journey to the “end of the earth” to “throw it

off” (Uys 15:03). Making this sort of decision is not necessarily an easy one;

that is, to most Western people. However, the Bushmen value their love and happiness

over having life made easier for them.

That the Bushmen came to the decision to rid themselves of the

Coke bottle so quickly shows how vastly different, and in a sense wiser, they

are than their Western society counterparts. Had those in the cities been faced

with a similar issue, that of having a single object to share in order

to make life easier, all hell would have broken loose. When one thinks of it,

that event reflects exactly what happened hundreds, if not thousands, of years

ago when Western civilization chose to make life “easier” while natives, like

the Bushmen, chose to value love and true happiness amongst each other. “Xi

understands that his people have two choices . . . progress or happiness. Our

ancestors chose the former, and the world has expanded . . . Xi and his tribe

make the opposite choice” (Kaston, par. 2). Our ancestors chose to make their

lives “easier” by inventing things, creating governmental systems, and

implementing different forms of employment. However, having all these elegant

social structures have made life harder rather than easier. Competition was

created, rich versus poor ideals formed, tension built over time, and life as

we know it has gotten to the point of there being more hate and jealousy than

love. This is not the case with the Bushmen; they care for each other, and make

sure that every individual is safe and satisfied. So, where did we go wrong?

We failed to ensure that our emotional well-being was

stable. We put so much pressure and care into making our physical lives better

that we never considered the emotional repercussions. Modern society has become

so fixated on the idea of improvement and conformity that we are more stressed

and depressed than ever. Just like Kate in Uys’ movie, we are being put into normal

jobs that will make us money but that also bring us despair. The only

difference is that we are scared to do anything about it. Kate takes a leap of

faith and decides to completely change her life by becoming a teacher for

children in Botswana after learning about the position through her journalism

job (Uys 25:58). Not many people in today’s society would even give that idea a

second chance, let alone go through with it. Unfortunately, we have become

programmed to adapt to the world around us. But Kate changed the programming

when she realized that it was off course. The main issue with our society’s

programming is that we are forcing a world to adapt to us, yet are never

truly satisfied with the changes.

Competition exists in just about every area of life. From the

social ladder to economic classes to the expensive items we buy on a daily

basis, competition stems from the idea that there always needs to be a new

advancement in technology. With this constant change, there is next to no room

for us as a society to learn and adapt to our new surroundings. With each new

iPhone or new version of Amazon’s Alexa or new autopilot car, like the Tesla,

that comes out, society grows ever-desperate trying to get these new pieces of

technology in their hands. The problem with this is that not everyone has the

availability to get it. But we make it important to have these new toys

and if one does not have it, they are automatically seen as less than. Our

self-value is based around the items that we can or cannot have. We will

consider ourselves to be less than those who can afford the next new and

improved “magic power devices” (KP). This need to adapt and conform to societal

standards has threatened us, yet we have not even noticed it.

The main focus of society’s worries and fears is judgment and

standing out. It is one of society’s (most specifically our generation’s) main

illnesses (Picciano, par. 2). We are so scared of being different that we will

conform to whatever society deems appropriate, regardless if we disagree with

it or not. This is especially seen within teens. It has become common for

“teenagers [to] conform to anything and everything to avoid standing out in the

fear of being judged or exiled by their peers, even if they do not agree to the

beliefs of the clique they have chosen to fit into” (Bhatia, par. 3). They will

do anything in their power to fit in and not be seen as an outsider. This is

the type of behavior that leads to the landing of “normal” jobs and living the

typical daily lives seen within The Gods Must Be Crazy. We thrive on the

idea that we need to be like everyone else and live a “full” life, which is

filled with next to no downtime set aside for personal care or growth. The

lives that we, and those “urbanites” in the movie, chose to live has turned

into this “Normative Social Influence: the idea that we comply in order to fuel

our need to be liked or belong” (Green 05:55). Psychologically speaking, we

want nothing more than to be seen as normal and follow whatever the current

trend is in society. This sort of behavior is nothing new, as psychologists

have been experimenting with the idea of conformity for over 60 years.

Solomon Asch, a social psychologist, conducted an experiment about

conformity back in the 1950s. The experiment consisted of putting a participant

in the same room as seven other “participants” (men who worked with Asch on the

experiment) and finding out whether or not the real participant would conform

to the answer that the other seven already agreed on. The participants had to

distinguish which comparison line matched that of the “target” line that Asch

presented to them. What Asch found was that, “On

average, about one third (32%) of the participants who were placed in this

situation went along and conformed with the clearly incorrect majority on the

critical trials” (McLeod, par. 11). Asch discovered through this experiment

that “People conform for two main

reasons: because they want to fit in with the group (normative influence) and

because they believe the group is better informed than they are (informational

influence)” (McLeod, par. 16). Despite knowing that the answer was wrong, the

men did not want to be seen as the “outsider,” so they went along with the

incorrect answer. It is this constant need and desire to

be like everyone else that we have lost a very important aspect to living a

decent life: happiness and love.

There is this so called “happiness famine” (Morrill, par. 5) in

society and it has caused us to lack empathy and love for each other. Most

importantly, it has caused us to lose happiness for not only others, but

ourselves. We are constantly wanting new “toys” and crave getting the newest

technological device. So, when we are unable to get them, we become unhappy

with ourselves, and after a while, it leads to self-hatred. Along with this, we

force ourselves to follow the “rules” that society has laid out for us: go to

school, get a degree, get a 9-5 job that will pay good money, get married, have

kids, buy a big house, be rich, and boom, we have the “perfect” life. The

problem, however, is that there is no such thing as a perfect life and because

of that, we will never be truly happy or satisfied with where we are in

life.

We have let this concept of a perfect life consume us. It has

gotten to a point where “stress consumes the population as everyone scrabbles

for that house with the picket fence which they never truly get to enjoy

because work is always hanging over them” (Morrill, par. 5). Because this is

what society says we should have, we feel horrible when we are unable to

have it. Unlike the Bushmen, we stress ourselves out trying to get the

“perfect” life that an imperfect society has carved out. What this has caused

is a dramatic shift in emotional and mental health, and causes distance between

us and our loved ones. We live believing that “modern society equals fullness

with meaning so if schedules are always booked then life must be wonderful”

(Morrill, par. 7). A majority of the time, we never have time for one another,

so we tend to not know what it means to love or to be happy. It has gotten to a

toxic point where because of this societal pressure to be like everyone else

and to have a full schedule, our mental health has worsened as a whole. This is

especially true within teenagers.

Teens are being crushed under the weight of needing good grades,

having a perfect social life, getting enough personal time for themselves, and,

worse of all, not being seen as an “outsider.” In Rush’s 1982 song,

“Subdivisions,” Neil Peart wrote, “Subdivisions

in the high school halls, in the shopping malls; conform or be cast out.

Subdivisions in the basement bars, in the backs of cars; be cool or be cast

out” (Rush). Peart was referencing how society has created these

so-called subdivisions in every aspect of life. This is especially true for

students in high school. There are numerous social groups that students get

placed into, and if one is to be placed in the “wrong” one, they are

automatically cast out and deemed unworthy. This is the experience that I had

growing up, not only in high school, but throughout my entire school life.

I was not like the “typical” girl, nor did I fit

in any mold that society (specifically the one I grew up in) had premade for

the different types of teenagers. This “typical,” ideal girl is the popular,

outgoing, kind, friendly, party girl with an ever so slight edge. I, on the

other hand, was the shy, overly nice, nerd, who loved the “wrong” music, and

was obsessed with theater. I was the outsider and people thought that

made me really weird, and for some time, I thought the same thing. This, then,

led to my mental health becoming severely worse than it already was, resulting

in an extreme case of anxiety and a very mild case of depression. But I am not

the only one who goes through this. Mental illness is being diagnosed more than

ever and it all stems from the society we live in, most specifically, the lives

we have forced ourselves to live.

Because we want the job that makes good money, we

get ones that are not necessarily what we dreamed for and end up dreading going

to work. We no longer pursue dreams and are scared to work outside of the

limits that society has set for us. However, we can live a life that we

want and desire. The only thing it takes is stepping outside of that social

norm. Take Andrew Steyn, for instance. He has a job that requires him to

analyze animal excrement, yet he is content and happy. He is a scientist, one who

is proud of where he is in life. Another example is when Kate makes the move to

the Kalahari. It is instantly recognized that she is more content being with

her students than trapped in the cubicle she used to work within. If we were to

follow in their footsteps, maybe we would learn true happiness again.

In order for our society to grow and help the

growing mental health crisis, we need to come together again to break these

societal norms. As a person who is doing her best to break those social norms,

I know how scary it is. I went from wanting to be a physical therapist to a

geneticist to being a filmmaker. I may have to struggle in order to live my

dream life and will have to work my butt off to make money, but I am okay with

that. I would rather be happy living a life doing something I love, something

that may mean sacrificing a larger paycheck, as opposed to a life where I am

unhappy, stressed, and despise my job.

If we are to have a society that loves and is

filled with happiness again, like the Bushmen, we need first allow ourselves to

open up and learn what we want in life. With this, we will find true happiness

within ourselves. This will, then, spread to each other and we will have a

society filled with love and respect and kindness. It is a hard thing to accept

but, “until our culture can

choose peace of mind over higher productivity, we will never self-actualize

like the Bushmen of the Kalahari Desert” (Kaston, par. 7). The moment we as a

society prioritize ourselves and those around us is the moment that we will

truly grow. But until that happens, we will be stuck in the harsh conditions of

Western civilization. The real question is, who will be the one to step up

first and break down the walls society has built around us?

Works Cited

Bhatia, Jill. “Teens struggle to

combat conformity.” Daily Records,

AsburyPark, 15 Feb. 2017 https://www.dailyrecord.com/story/opinion/letters/2017/02/15/teens-struggle-combat-conformity/97896120/

Ebert, Roger. “The Gods

Must Be Crazy” RogerEbert.com, Roger Ebert, 1 Jan. 1981. https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/the-gods-must-be-crazy-1981

Gordon, Paul Kirpal.

Various class Discussions

Green,

Hank, director. Social Influence: Crash Course Psychology #38. YouTube,

YouTube, 11 Nov. 2014, www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=12&v=UGxGDdQnC1Y.

Kaston, Brandan. “The Price of Happiness is Actually Free” Taking

Giant Steps, 2 Nov. 2018, https://giantstepspress.blogspot.com/2018/11/the-price-of-happiness-is-actually-free.html

McLeod, Saul. “Solomon Asch - Conformity Experiment.” Simply

Psychology, Simply Psychology, 28 Dec. 2018, www.simplypsychology.org/asch-conformity.html.

Morrill, Morgan. “The Ironic Hospitality of the Kalahari Desert” Taking

Giant Steps, 14 Mar. 2018, https://giantstepspress.blogspot.com/2018/03/the-ironic-hospitality-of-kalahari.html

Picciano, Kelsey. “Just Another Loose Brick in the Wall” Taking

Giant Steps, 16 July. 2016, https://giantstepspress.blogspot.com/search?q=just+another+loose+brick+in+the+wall

Rush, “Subdivisions”, Signals,

Terry Brown, Le Studio, Quebec, 1982

The Gods Must be Crazy. Directed by Jamie Uys, performances by N!xau, Marius Weyers, and Sandra Prinsloo. 20th Century Fox., 13 July. 1984. 123Movies