𝙑𝙖𝙡𝙚𝙣𝙩𝙞𝙣𝙚’𝙨 𝘿𝙖𝙮 𝚒𝚜 𝚞𝚜𝚞𝚊𝚕𝚕𝚢 𝚜𝚘𝚕𝚍 𝚊𝚜 𝚊 𝚝𝚒𝚍𝚢 𝚜𝚝𝚘𝚛𝚢: 𝚕𝚘𝚟𝚎 𝚊𝚜 𝚌𝚘𝚖𝚏𝚘𝚛𝚝, 𝚕𝚘𝚟𝚎 𝚊𝚜 𝚜𝚠𝚎𝚎𝚝𝚗𝚎𝚜𝚜, 𝚕𝚘𝚟𝚎 𝚊𝚜 𝚜𝚊𝚏𝚎. 𝙱𝚞𝚝 𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚔𝚒𝚗𝚍 𝚘𝚏 𝚕𝚘𝚟𝚎 𝚕𝚒𝚝𝚎𝚛𝚊𝚝𝚞𝚛𝚎 𝚔𝚗𝚘𝚠𝚜 𝚋𝚎𝚜𝚝 𝚒𝚜 𝚛𝚊𝚛𝚎𝚕𝚢 𝚝𝚑𝚊𝚝 𝚘𝚋𝚎𝚍𝚒𝚎𝚗𝚝. 𝙸𝚝 𝚒𝚜 𝚊𝚙𝚙𝚎𝚝𝚒𝚝𝚎 𝚊𝚗𝚍 𝚜𝚙𝚎𝚕𝚕𝚠𝚘𝚛𝚔; 𝚒𝚝 𝚒𝚜 𝚊 𝚏𝚘𝚛𝚌𝚎 𝚝𝚑𝚊𝚝 𝚌𝚊𝚗 𝚑𝚎𝚊𝚕, 𝚞𝚗𝚖𝚊𝚔𝚎, 𝚊𝚗𝚍 𝚍𝚛𝚊𝚐 𝚞𝚜 𝚒𝚗𝚝𝚘 𝚙𝚊𝚛𝚝𝚜 𝚘𝚏 𝚘𝚞𝚛𝚜𝚎𝚕𝚟𝚎𝚜 𝚠𝚎 𝚝𝚑𝚘𝚞𝚐𝚑𝚝 𝚠𝚎𝚛𝚎 𝚕𝚘𝚗𝚐 𝚝𝚊𝚖𝚎𝚍.

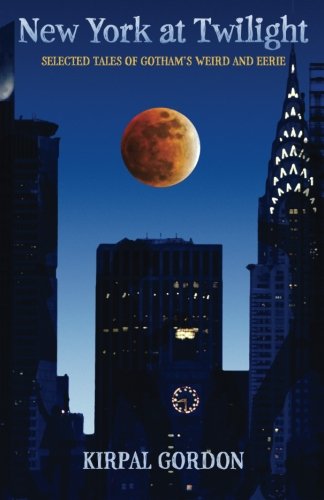

𝙵𝚘𝚛 𝚝𝚘𝚍𝚊𝚢’𝚜 𝚅𝚊𝚕𝚎𝚗𝚝𝚒𝚗𝚎’𝚜 𝚙𝚘𝚜𝚝, 𝚠𝚎’𝚛𝚎 𝚜𝚑𝚊𝚛𝚒𝚗𝚐 𝙲𝚑𝚊𝚙𝚝𝚎𝚛 𝟷, “𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝗠𝗮𝗴𝘂𝘀 𝗼𝗳 𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝗕𝗹𝘂𝗲 𝗛𝗼𝘂𝗿,” 𝚏𝚛𝚘𝚖 𝙉𝙚𝙬 𝙔𝙤𝙧𝙠 𝙖𝙩 𝙏𝙬𝙞𝙡𝙞𝙜𝙝𝙩: 𝙎𝙚𝙡𝙚𝙘𝙩𝙚𝙙 𝙏𝙖𝙡𝙚𝙨 𝙤𝙛 𝙂𝙤𝙩𝙝𝙖𝙢’𝙨 𝙒𝙚𝙞𝙧𝙙 & 𝙀𝙚𝙧𝙞𝙚 — 𝚊 𝚗𝚘𝚒𝚛-𝚕𝚢𝚛𝚒𝚌𝚊𝚕 𝚙𝚕𝚞𝚗𝚐𝚎 𝚒𝚗𝚝𝚘 𝙼𝚊𝚗𝚑𝚊𝚝𝚝𝚊𝚗’𝚜 𝚕’𝚑𝚎𝚞𝚛𝚎 𝚋𝚕𝚎𝚞𝚎, 𝚠𝚑𝚎𝚛𝚎 𝚏𝚕𝚒𝚛𝚝𝚊𝚝𝚒𝚘𝚗 𝚝𝚞𝚛𝚗𝚜 𝚖𝚢𝚝𝚑𝚒𝚌, 𝚍𝚎𝚜𝚒𝚛𝚎 𝚝𝚞𝚛𝚗𝚜 𝚙𝚛𝚘𝚙𝚑𝚎𝚝𝚒𝚌, 𝚊𝚗𝚍 𝚛𝚘𝚖𝚊𝚗𝚌𝚎 𝚠𝚊𝚕𝚔𝚜 𝚑𝚊𝚗𝚍-𝚒𝚗-𝚑𝚊𝚗𝚍 𝚠𝚒𝚝𝚑 𝚖𝚎𝚗𝚊𝚌𝚎. 𝙰 𝚐𝚊𝚕𝚕𝚎𝚛𝚢 𝚘𝚙𝚎𝚗𝚒𝚗𝚐, 𝚏𝚛𝚎𝚎 𝙼𝚊𝚒 𝚃𝚊𝚒𝚜, 𝚊 𝚛𝚊𝚒𝚗-𝚐𝚕𝚘𝚜𝚜𝚎𝚍 𝚜𝚝𝚛𝚎𝚎𝚝, 𝚊 𝚃𝚑𝚊𝚒 𝚃𝚢𝚐𝚎𝚛 𝚖𝚊𝚣𝚎: 𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚗𝚒𝚐𝚑𝚝 𝚔𝚎𝚎𝚙𝚜 𝚠𝚒𝚍𝚎𝚗𝚒𝚗𝚐 𝚒𝚝𝚜 𝚊𝚗𝚐𝚕𝚎 𝚞𝚗𝚝𝚒𝚕 𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚠𝚒𝚕𝚍𝚎𝚛𝚗𝚎𝚜𝚜 𝚒𝚗𝚜𝚒𝚍𝚎 𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚜𝚎𝚕𝚏 𝚜𝚝𝚎𝚙𝚜 𝚏𝚞𝚕𝚕𝚢 𝚒𝚗𝚝𝚘 𝚏𝚛𝚊𝚖𝚎.

I read Honey’s text: “Lady X, it’s my 1st show in ritzy 57th St gallery & rum sponsor is handing out Mai Tais—nothing to do with my work wtf—I feel unseen so if out drop by.”

I need escape. I’m ready for some fun with Honey.

I sense a cold coming on and free Mai Tais will help me weather that approaching storm while I contemplate my last essay in a ten-part series which asks: If civilization is annihilating the wilderness, what happens to the wilderness within us? I’m thinking Central Park’s two blocks from Honey’s gallery and scary as hell after dark so wandering around high on Mai Tais may bring the wilderness out in me.

I walk out into the day’s fading light. I hail a taxi.

I arrive at the gallery early and grab a Mai Tai. I wander from room to room, thrilled to have such excellent views of the work, relieved that the herds have not yet gathered.

I’m totally knocked out by Honey’s show, “How Boundless Love Seams,” ten photos of a man and a woman running toward one another open armed and exuberant. But each photo widens the angle and reveals other people—outraged spouses, shocked children—in their midst. And because she shows me love’s power to create and destroy in the same image, I’m thinking Love is the first clue for the wilderness-within-us article.

Honey looks great in her custom cobalt blue jumpsuit. She waves me over.

She gushes at my non-stop stream of compliments. She turns and I see who has been chatting her up—a black-haired babe magnet—and she says, “Lady X, this is Mr. Y, a photographer.”

She’s called away, and suddenly alone with him, I’m thinking Photographer? Please, he’s an actor playing a Y chromosome.

I sense heat nevertheless. I feel my skin start to breathe.

I check his good teeth, Roman nose, rugged face, dimpled chin. I scan the longish wavy mane, brown corduroy jacket, black elbow patches, safari shirt, top buttons opened, chest hair spilling out. His smile says I’ll make you come, so I’m naturally turned on—he’s both manly specimen and cliché—but philosophically opposed. I’m thinking So he can rattle my teacup but can he talk afterwards?

He starts talking: “I can’t stop thinking about you, Lady X, and your article in the Village Voiceless last week, how we’re twenty plus years into a new century and more embarked than ever on a wave of mass extinction that’s wiping out half of the planet’s ten million species of plants, animals and fish. I agree with you that Gaia, mother of us all, might, like pulling a tick out of her armpit, exterminate us to save what’s left of life on Earth. We’re acting like reptiles and refusing our role as eco-steward homo faber mammals—but if nature can be carefree, why can’t we?—so I keep returning to your conclusion that our consciousness is not separate from other species and the sounds we make in the sexual abandon of la petit mort are the death knells of the species we’ve made extinct by our compulsive reproduction and abuse of natural resources.”

He loves my work. He quotes me verbatim, huzzah!

He gets my twisted sense of humor but then he blurts out, “Listen, I need a minute to get myself together because you’re standing so close to me and you look like how you read, that is, breathtakingly beautiful and so alive, it’s like your skin is open, so let me cool off and calm down and get us both another Mai Tai.” I finally catch on: Mr. Y is no one-note samba he-man but a total charm boat, spontaneous, unafraid to share his feelings, and for the first time this evening I’m glad I’m wearing a little black dress, badass heels and bling.

He takes my red plastic cup and the back of his hand brushes against my chest—I’m thinking Accidentally?—and my foolish nipples harden to his touch. As he disappears into the crowd, I want to lunge after him but I slow the breathing and check the mascara. He returns with refills and looks at me with these probing dark brown eyes.

We down more Mai Tais. We hit the street with a blazing buzz on.

We reach for the other’s hand at the same time. We saunter down Eighth Avenue and I say, “Manhattan is suspended in what you photographers call l’heure bleue” and he says, “What would you call this hour” and I say, “‘Twilight, a timid fawn, went glimmering by’” and he adds, “‘And Night, the dark-blue hunter, followed fast’” quoting George William Russell’s “Refuge” back to me as if he could read the words from my mind—as if destiny were guiding our meeting.

“We’re on the same wavelength,” he says so candidly that I start to melt a little, “and I should admit that I imagined you as loving daring charming and in person you’re all that times ten, Lady X.” These words find me arm in arm with him, and in company so assuring, I’m thinking We’re a great fit and he’s really built for speed.

He slows down. He stops a block later.

He looks as if he were under my spell. He seems willing to do anything for me so I move us out of view of pedestrian traffic and ask him to look the other way. I step out of my panties, slip them into my purse and snuggle into him, and as we start walking, the summer wind caresses me down there which sends the joyous abandon coursing through my whole body.

He asks me with such genuine concern—two blocks later when my heavy breathing gives me away—if I’m all right and I’m thinking Mr. Y is the magus of the blue hour filling me with his magic; I’m under his spell!

I pull him aside. I put the palm of my hand over his heart.

I get misty when he wraps his corduroy jacket around me which smells so inviting, so him, and he holds me closer which feels so good as we stroll, and as a gentle rain falls from the purple-blue sky, he looks so virile with the ends of his curly hair dew-dropped and his shirt a little damp. I’m thinking It’s either going to be steamy sex in a Hell’s Kitchen vestibule that we’ll regret later or another drink right now.

I stop under a chic sign in red neon spelling Thai Tyger, pinch his nipples with my fingertips—because I’m getting too hot to handle—and whisper, “I’m awfully hungry! Let’s nosh, no? Another Mai Tai or two, Mr. Y?”

His eyes glaze over. His face drops.

His head hangs, his body appears paralyzed, as if eating here would be the worst thing that could possibly happen, but alcohol is involved so I barge through the door on my own and follow the maître d’ past a long aquarium and teakwood bar which leads into a maze of flat black walkways without clues as to where the restaurant begins or ends.

His manners return, he catches up and we swivel into a small private booth with odd angles of track lighting that reveal a large oil painting framed in ornate gold-leaf of the Queen of Siam—beaming regally, colors pulsing—and his pouting face, so I’m thinking Is it already over with Mr. I-Yi-Yi?

He takes a long drink of water. He gathers himself.

He high-beams me the promise of sexual healing, not about to let my restaurant choice foil him. He says, “You see the whole mess we’re in, Lady X: While the Lake poets revered nature, walked the woods and wrote the Romantic movement into being, the English navy carved up Asia and Africa whose reverence for nature was considered backwards and legitimated their conquest. Our treatment of women and lack of reverence for nature go hand in hand making it only more unfortunate that the only remaining path to reverence our culture takes seriously is the passion of erotic ecstasy as you pointed out.”

Mr. Y is reading me like a psychic and I’m thinking Such relentless chutzpah—using my own writing to seduce me.

I’m sense the deep tingle now. I’m past my philosophical opposition.

I’m wondering how he keeps growing more attractive. I see I’m-a-better-future-for-your-children written all over him, and though I don’t want children now or ever, his strong upper body, chiseled features, shapely frontal lobes above his brows, that thick head of black hair and scent of a hunter cause impulses long dead, nearly extinct, to awaken passionate erotic ecstasy within me.

I’m full of grave misgivings about overpopulating a planet but I’m still a woman, and now that I know that I want him, I have to get up and move around or just undress him right here in this private booth so I shush his half-hearted objection, unbuckle his belt and unzip him. Although I like where this is going—accuse me of bait and switch, I’ve been called worse—I stand up, make a T with my hands, walk down the corridor to the far end of the bar by the aquarium. And all right, sue me, a few of my friends who know I work late and appreciate meeting for a drink after hours and no, I don’t sleep with all of them but yes I’m thinking Better check my phone messages and clear the deck just in case.

I see his questioning look upon my return. I owe him an answer.

I close his eyes and open my purse. I turn on my tape recorder to get his truth on record, slide closer until we’re leg to leg, pick up my Mai Tai, open his eyelids and say, “To nothing pressing, Mr. Y.”

I clink rims with him and lock eyes and now the mating dance is on for real. I’m delighted when the waitress returns because—without breaking eye contact with me—he speaks to her in Thai and they laugh and she disappears, and in the heightened silence that sexual arousal and Mai Tais provide, I undress him in my mind but I’m thinking I’m not sure what to do next.

I run my hands through his hair. I part his lips with the push of my fingers.

I open his mouth wide and French kiss him. I feel kind of sexy in this dark booth, but I’m distracted by his bulging-throbbing-springing thing out of his unzipped pants and decide the best move is to bring relief. I get on my hands and knees and go down on him under the table, but as I take him in my mouth, I get a charley horse in my left leg.

Although we laugh, I know this looks bad and as he massages away the cramp, I’m thinking I don’t want to lose my appetite or my reputation but I must get a grip, at least find out his first name.

I check the waitress setting down soup and dumplings. I catch her looking at Y.

I ask Y how well he knows this joint. “I know it through Zee,” he says, “a friend from my old Brooklyn neighborhood in Bensonhurst. Zee left my mother a message and told me to meet him here but get this: I had just returned from Thailand and no one knew because I had been off the radar having fled New York to avoid a death threat I had received while employed by a private investigator who collected evidence on extra-marital affairs. I had taken photos detrimental to a celebrity known for vengeance—I’m not going to say who—only that if I’d been told all the details, I never would have tailed this whack job in the first place. But at least the boss called to tell me he had given me up and that I had about an hour to get out of town. So on the plane I resolved never to work for anybody but myself and to never use photography, the true love of my life, against anyone. I shaved my head, practiced meditation, wandered the jungles, made pilgrimages to retreats deep in the Thai wilderness, and because, as a student, Ansel Adams’ Zen-like landscapes and Minor White’s foreground-background switcheroos were like lifelines, I felt I deserved my exile for almost destroying a man with my photographs, the result of abandoning my artistic calling to pay the rent.”

I’m thinking Y’s journey is the last article’s ontogenic-phylogenic journey: his life in civilized society leads him to need money which leads him to misuse his artistic gift which leads to death threats and his exodus into the jungle wilderness which leads to his atonement with nature and leads him to re-inhabit civilization and return to the city that ran him out. He’s our uncertain future.

I feel like I am seeing Mr. Y clearly for the first time. I want to tell him so.

I see the waitress return with chicken in basil. I’m sure these two know each other.

I ask him what happened with Zee. “I answered all Zee’s questions about my meditations and monasteries,” Y says, “and then Zee asked if there were any wild animals left because his only fear was the white Bengal tiger, worshipped in Bengal and Thailand during the moon’s crescent phase as the incarnation of Shiva, the destroyer of the illusion we’re enveloped in. I told Zee I had no idea and I heard no more of him until a year later. A package arrived addressed to me which my Sicilian mother called mallocchio—the evil eye—and gave her bad dreams. So I rushed over, opened the package and inside was a broken camera which contained a roll of film that I took into the dark room and developed. The first shots were of Zee in tourist scenes but the last ten shots revealed a white Bengal tiger: hiding in the jungle, walking into the open, leaping toward the camera, then with the right arm of Zee in its mouth and the very last frame blank.”

I’m thinking Zee’s photos are the coda to the last article on the existing wilderness: humans need to honor other species’ territories; mother nature has spoken.

Mr. Y starts to break down. He looks up at me wide-eyed.

He’s changed from a Y chromosome to the word Why. He asks, “What does it mean that you and I are sitting here in the same restaurant at the same table eating the same dishes as Zee and me, Lady X?”

Mr. Y looks aghast when I tell him, “Our desire is a ‘fearful symmetry’ as William Blake called his tyger tyger burning bright. And our arriving in the Thai Tyger at this table eating these foods means it’s time you got off the wheel of repeating behaviors, that is, you’ve used your art as a weapon once—and have been hunted ever since—so come to my place; it’s a safe haven. No one will find you and I can hold you.” I’m thinking Did I over-pitch?

“I’m under the curse of Zee,” Mr. Y cries. I pay him no mind.

I lick his tears away. I put my lips on his thick lips and hope for the best.

I start getting swept up into the delicious tongue and groove play and it’s really getting wet down below and my nipples are protruding like bullets against the tight stretch dress—call me a tease, whatever—but I’m thinking My bladder’s about to burst. So I break away from his clutches, grab my purse, put my finger on his lips, walk a long time this way and that, then stop at the end of the maze and face two doors marked only in Thai.

I open Door Number One. I enter a large outdoor garden.

I am drawn in by the luscious fragrance of gardenia. I step up onto a metal walkway that winds through a forest of large exotic ferns, but my heel soon gets caught in the grating. Although I’m standing immobile—unable to get my foot out of the shoe or the heel out of the metal grid—I’m thinking I should have asked Y more about the curse of Zee because above me a crescent moon has risen in a clear sky and below me sits an altar adorned with images of Shiva Nataraj.

I can just make out in the distance the shape of a white Bengal tiger fast approaching against the rapid staccato clicks of a high-speed camera.

🛒 𝐆𝐞𝐭 𝐲𝐨𝐮𝐫 𝐜𝐨𝐩𝐲 today: 𝙉𝙚𝙬 𝙔𝙤𝙧𝙠 𝙖𝙩 𝙏𝙬𝙞𝙡𝙞𝙜𝙝𝙩 on Amazon 👇

Available on Amazon

New York at Twilight

Selected Tales of Gotham’s Weird & Eerie

A collection of twilight-zone NYC tales—eerie, lyrical, and strange.

View on Amazon →

(Link opens in a new tab.)