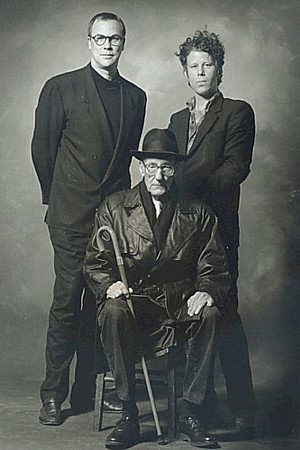

Anne Waldman and Jim Cohn, Naropa University, 2009. Photo by Jack Greene

KIRPAL GORDON: The first two stanzas of “Even Now, As You Enter My Poems,” the opening verse in your most recent book, Mantra Winds: Poems 2004-2010, read like an introduction into your entire oeuvre of eight spoken-word rock-blues-jazz CDs, three books of non-fiction, six poetry collections and a truly remarkable amount of internet scholarship at The Museum of American Poetics:

“Without end or beginning---this is how it is,

Inimitable, exactly as you are,

Even now, as you enter my poems,

As you whisper in my ear

Of thighs entwined, lips your lips did kiss.

Who can say which way is not onward?

(All loves are the way onward.).”

For me the beauty you see in the face of impermanence and of love as the basic human navigation strikes me not only as an Ars Poetica but a way to appreciate the unity behind the different forms you are using. What are you working on now?

JIM COHN: I think these times show no more a sense of unity behind the different forms as any other time. There’s always the shattering of the false idol of otherness mosaic of humanity. It’s unbelievable what people say or believe. Am I suppose to believe I’m an anarchist unwilling to face the need to organize? When I was a teenager, I was mesmerized by Bob Dylan’s long poem “Ballad Of A Thin Man.” The famous line of the song––“Something is happening here, but you don’t know what it is...”––seemed like an attack. Today, although it still seems like an attack, I see it more as a series of veils. The outermost veil is the attack. The vernacular speech provides the second veil. The third veil is where the attack is seen as a statement, a universal. The statement regarding things happening that we do not understand is the third veil––there, the ego disguise dissolves into compassion. If you tell me there are two kinds of people in this world–– “stick” people or “carrot” people––the former needing confrontation, the latter conciliation––what am I suppose to say? If you tell me there are those who ask themselves “Would that one hide me from those coming for me or turn me in?” How am I to respond to that? My writing has its own unknown citizenry. I write to them.

Right now, I’m finishing up a manuscript of new poems to follow my 2010 book Mantra Winds, a selected poems manuscript that has me returning to the last 35 years of poetry making, and a selected prose manuscript to distill my three books of prose: Sign Mind, The Golden Body, and Sutras & Bardos. At this point in my current existence, I interpret writing principles with more depth than I did earlier when first struck by them. For example, the famous 1927 line from William Carlos Williams’ epic poem Paterson, "No ideas but in things," suggests to me that the best poetry does not dwell on why things are happening, but what actually is going on, right now. Another example of deepening consciousness through writing over time is how I look at Allen Ginsberg’s writing slogan "Mind is shapely, Art is shapely," found in his 1986 poem “Cosmopolitan Greetings.” Except for my first major book of poems, Prairie Falcon, I have assembled poems for books in chronological order in order to be mindful of the natural causality or shapeliness or artistry of things as they come up. What I like about editing my own selected poems is that a timeline approach gives rise to the hidden connections that emerge as the individual books are lashed together as one. Now that I'm piecing together inter-book poems, I see a whole other metanarrative––the one that spans an artist's life.

That is, each book is an emanation. Each book is a past life. You can revisit the periods of each book as though each were a past life, and you can revisit between one book and the next as you would a between lives regression. Just like in this life, where you can get an understanding that you didn't exactly come into the world as a blank slate, so in the life of a poet, you don’t create each new work in pure emptiness. In fact, there was more intention and burden that called you into the world than not. And there’s more awareness and suffering that we bring to each book creation than not. So, looking at the a pile of books you completed early when you are later in life, you begin to experience the relationship you have cultivated over a lifetime to a higher narrative––a narrative that is more aligned to the higher truth that brought you into the world in the first place. You may have been in human form 537 times before this life. You may be your mother or father, your daughter or son in some other dimension, some other universe, some other incarnation. For me, I've see how invention and imagination, candor and clear hard images have informed and continue to inform my work, whether I'm looking backwards or forwards, inwards or outwards, from the standpoint of extraterrestial or earthling. And most interesting to me is the shifting experience of the "I" complex at the heart of all our troubles. In my current work, I am dedicated to an "I" that ends karma, based upon Anne Waldman’s 2011 feminist epic The Iovis Trilogy, the first great poetics gift to the 21st century. This shift in identity politics reflects a major contribution of poetry in the postbeat era.

On the digital poetics media front, I continue to develop the Museum of American Poetics (MAP) at http://www.poetspath.com/, which I founded in 1998 after having a dream the night Allen Ginsberg died at home on April 5, 1997. Recently, in the fall and winter of 2011, I collaborated with Zhang Ziqing, professor of Foreign Literature, Nanjing University, on adding a number of 20th and 21st century Chinese poets to MAP’s international exhibits. I also documented the Occupy Wall Street New York General Assembly “Declaration of Occupation of New York City,” and expanded the MAP Channel at YouTube with literary arts productions ranging from the Tunisian rapper El General to Herbie Hancock and Leonard Cohen doing Joni Mitchell’s “The Jungle Line” to John Trudell talking about poetry and politics to rare footage of Jack Kerouac with Cat Power’s “Good Woman” as musical accompaniment. With MAP, I continue to give ample evidence for the inclusive and multidimensional postbeat movement. Besides maintaining and expanding twenty-four exhibits that highlight the diversity of American poetry, I continue editing my annual poetry magazine Napalm Health Spa, now entering its twenty-second year of publication.

KG: Talk to me about Sutras & Bardos, a collection that took me to school, Jim. Your personal recollections of Allen Ginsberg, the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at Naropa University then and now, the relation of poetry to meditation, the work of Anne Waldman, and the “diaspora” or de-centralization of the postbeat into the literature of sign language, feminism, surrealism, post-modernism, the avant-garde, African-American and other lineages of color, all of which you call the New Demotics, caused me to re-think what I thought I knew. I was moved by your appreciation of Whitman and I wonder what your thoughts are regarding the poet as social and aesthetic critic in the lineage of William Carlos Williams-Ezra Pound-Ginsberg-Waldman. I also read on your Facebook page that Wikipedia had a problem with your use of the term postbeat.

JC: Sutras & Bardos: Essays & Interviews on Allen Ginsberg, The Kerouac School, Anne Waldman, The Postbeat Poets & The New Demotics involved a good deal of contemplative thinking, especially the second half, on the postbeats. As a poet interested in the American outrider poetics tradition first described by Whitman and running through Williams, Pound, Ginsberg, and Anne Waldman, I was interested in writing about a social and aesthetic vision of contemporary poetry that although rooted in 20th century experimental literary movements, is unique in its own right and worthy of scholarly analysis and critical praise. My collection of essays associated with the idea of “postbeat” grew out of an unpublished anthology I’d edited in 2004. Assuming American publishers would have no interest in it, I sent an email to Wen Chu-an, a respected Chinese translator of Kerouac and Ginsberg who is credited with bringing Beat Generation literature to China, to ask if he’d be interested in helping me bring a collection of postbeat poetry into print. I had come up with the idea of writing Wen Chu-an after receiving a copy of his 2001 Chinese/English bilingual edition of Howl: Allen Ginsberg: Selected Poems (1947-1997) as a gift from Beat Generation book collector, Walt Smith.

The history of the term “postbeat,” which to me signifies the demotic and expansive elements of poetry after the Beats, wasn’t just something I made up in a vacuum. Within my own circle, a loosely affiliated community who’ve been referred to by poet Marc Olmsted as the “heartsons and heartdaughters of Allen Ginsberg,” I gathered ethnographic data of those social, political, cultural, sexual, aesthetic and technological differentiations that best signify the context of postbeat literature and times. The poets I sought input from included Antler, Andy Clausen, David Cope, Eliot Katz, Lesléa Newman, Marc Olmsted, Thom Peters, Jr., Jeff Poniewaz, Joe Richey, Randy Roark, Steve Silberman, and Anne Waldman, as well as Peter Hale and Bob Rosenthal at the Allen Ginsberg Trust, and Bill Morgan, Allen’s bibliographer and editor of several posthumous Ginsberg works. These discussions took place around 2003-2004.

Only later, after Wen Chu-an suddenly died unbeknownst to me, did I come across the work of poet Vernon Frazier on the “post-beats.” Frazier’s work really surprised me for three reasons. First, he was using the “post-beat” terminology similar to my useage of “postbeat.” Second, unknown to me, he had edited his own anthology of “post-beat” poets including many poets I had never heard of, and he’d sought Chinese, not American, publication of the work. Third, he had been working on his post-beat anthology with Wen Chu-an all the while I had been corresponding with Wen about doing a similar project. What kind of coincidence was that! So, totally unknown to one another, we were like two mad scientists coming up with similar theories regarding the unknown––in our case, the literary unknown. We were also both working in the tradition of earlier 20th century poet scholars such as Pound, Stein, and Williams to not simply write poetry, but also to activate freedom through naming. Yet we both had a different sense of Beat legacy and distinct poets that illustrated or modeled those legacies. And I think I understood intuitively that there is no monolithic Beat legacy––a poet may be rooted in Kerouac or Burroughs, another in Corso, in Cassady, another in the women of the Beat Generation, another in poets of color associated with the Beats. And of course, there were the poets who received direct transmissions from Ginsberg.

Leave it to the Chinese to provide First Analysis to this after-the-beats genre of twenty-first century American and World poetries. I mean, no American publisher would gamble on that. With David Cope, we re-edited my original anthology of postbeat poets and sent the manuscript out to sixteen or seventeen publishers. One after another, each publisher shot it down. Around the same time, in 2007, Shanghai Century Publishing released Frazier’s Selected Poems by Post-Beat Poets. As I’ve said, I was completely unaware of any “post-beat” anthology coming out of China in bilingual edition because Wen Chu-an never bothered to disclose that he was already at work on one. Instead, Wen cultivated a sense that he’d find a Chinese publisher to do my anthology as well. Crazy, but true. In fact, the whole idea for the title Sutras & Bardos came to me as soon as I decided to self-designate “postbeat” as a way to talk about the spiritual metanexi drawing together world revolutionary poetics traditions inciting a mass-metamorphosis of the first true global poetry. That decision led to my Wikipedia entry “Postbeat Poets” and its publication on January 8, 2008. And it wasn’t until after that entry was published that I found Vernon’s essay “Extending the Age of Spontaneity to a New Era: Post-Beat Poets in America,” published in Michael Rothenburg’s online Big Bridge #10.

November 30, 2011, almost three years after the publication of my “Postbeat Poets” essay, two editors at Wikipedia decided to delete it after they unilaterally and incorrectly determined that the term “postbeat” was a neologism, that my Sutras & Bardos mentioned the term only in passing, and that there is no such thing as a Postbeat movement. I strongly disagreed with these editors’ decision and responded to them point by point to no avail. They just took it down. With all the people in the world unable to get rid of links to personal data they wish would go away, I had the experience of Wikipedia removing my entry under the guise of policing against the “postbeat” being some kind of hoax. I’m always somewhat shocked when some big news story breaks and with it the phenomena of a new instantaneous Wikipedia entry––I’m thinking of their page on the killing of Osama bin Laden as an example. Where was the proof of that event? Once we reach the point where poets lose control over naming their own literary movements to technologic forces such as Wikipedia, clearly a more powerful force than even the academy, anything unacceptable or threatening to the technojuggarnaut can be dismissed. I don’t accept their actions, but I accept the reality that “Postbeat Poets” was censored out by Wikipedia. I would suggest that both Frazier’s and my work on the postbeats/post-beats remains a cornerstone for future scholars interested in our time and our poetry.

KG: Although I’m not a Buddhist, I am aware of the Vajrayana concept of merging wisdom (prajna) with skillful means (upaya). As a savvy skill means warrior, you seem particularly adept at digital Dharma, especially at MAP, which is like a loka or heavenly abode shining radiant grace. What are your thoughts on global expansiveness and the use of technology in the postbeat era?

JC: With our wounded earth connected through technology, the quantitative aspects of languages are the new currency. No country can conduct secret wars, secret atrocities, secret holocausts anymore because there’s somebody everywhere with the means to report on it by means of personal mobile technology and social networking. There are now so many complimentary or interacting poetries available to us, not simply internationally, but domestically as well, that it seems the quantitative is the only way people can begin to comprehend and organize the magnitude of knowledge available. But as William Carlos Williams posited at the turn of the twentieth century, these quantitative measures are merely the secondary characteristics of language. Poetry is language’s primary force. By that, he was suggesting the quality of mind that is lodged in imagination.

It’s impossible to deny that the postbeat era’s relationship to technology is one that is unlike any previous generation in history. Technology plays a key role in defining the postbeat landscape insofar as we are the first technologically savvy poet warriors of anything approximating a digital Dharma. By “digital Dharma,” we’re talking about metaphors of consciousness related to the Infosphere––cameras that provide “deep seeing,” film as a reflection of soul, a cloud that suggests new ways of understanding the transpersonal, the internet as mindfulness, chakras of communications as guides to Wisdom 2.0, telephone reality as an aspect of dream states, new media as evolving into one global brain, Twitter as an awareness practice, the infosphere itself as the beloved. We all have to start someplace on this path that is increasingly influenced by rapid technological change. And we need to realize that technologies are native to every stage of human history. The key thing is technology that is used to engineer human docility or enslavement will have its own dark karma.

KG: What about generational legacy? Can the so-called baby boomer generation effectively carry out the mission of the Beats or am I looking backward instead of forward?

JC: Generational legacy looks at what is passed along collectively. In Sutras & Bardos, I describe features of postbeat legacy based on specific values Ginsberg described as pertaining to the Beat’s impact––an enhanced and interconnected sense of social justice being a case in point. I began thinking about my generation’s legacy in my late 50s, perhaps in parallel with the death of my mother and cleaning out her townhouse, as well as my home literary archives and library, and my own end of life considerations. It occurred to me that special collection libraries I have loved visiting––the National Archives for the Ezra Pound Papers, the University of California at San Diego for Paul Blackburn’s Papers, and Stanford University for the Allen Ginsberg Papers––may have no interest in collecting the papers of the postbeats. I may find that there is no one to carry on the Museum of American Poetics, which would be a loss. It also occurred to me that these brick and mortar institutions may also be irrelevant by the time the last baby boomer takes her last breath. When you can upload your own scanned archives directly to your own author page, interested audiences can access your literary works without any filtering. Perhaps the most salient aspect of postbeat generational legacy is that it was by and large a chaotic, diverse, multiplatformed, and not necessarily coherent indy-spirited world literary movement.

KG: So how can Giant Steps readers stay connected with all of what you do?

JC: Ah! So let’s run with that history for a moment... Giant Steps is the fifth studio album by saxophonist John Coltrane, released in 1960 on Atlantic Records. It’s known as the breakthrough recording for Coltrane as a band leader. In 2004, it was one of fifty recordings chosen by the Library of Congress to be added to the National Recording Registry. The particular tune “Giant Steps”––which opens the album––exemplifies Coltrane’s melodic phrasing that came to be know as “sheets of sound”–– developed while playing with Miles Davis and Thelonius Monk in the late 1950s, which corresponds to the period of fervid Beat literary invention inspired by jazz improvisation––and features third-related chord movements that came to be known as “Coltrane changes” or the “Coltrane Matrix” or “Coltrane Cycle” or the “Countdown formula” or the “Giant Steps chord progression.”

So, by “Giant Steps readers,” we’re also talking about those who see themselves holding the space of a poetics associated with Ezra Pound whose modernist battle cry was “Make It New”––where “It” suggests bringing into the present that which is valuable in the cultures of the past, and “New” refers to our own awareness breathing life, its vividness and emotion, into a line of artistic and intellectual accomplishment. We’re talking about practitioners or students or lovers of poesy who are knowledgeable enough or intuitive or psychic enough to reject literary traditions that seem outmoded and diction that seems too genteel to suit an era of technological breakthroughs and global violence. We’re referring to mind that is fundamentally questioning and reinventing their art forms. We are also speaking of works of art that are a beginning, an invention, a discovery––as in the meaning of the name Troubadour, a finder. Vajrayana Buddhists, and I’m thinking about Trungpa Chögyam Rinpoche and his Crazy Wisdom and Mishap Lineage transmissional relationships through Naropa and the Kerouac School with both Allen Ginsberg and Anne Waldman––and through them with many of the postbeats––believe that within our lives, our bodies, lie “treasures for heaven” or embedded truths that we may both deposit and retrieve through awareness within ourselves and the world around us. The name given to these embedded truths are termas which mean earth treasures, mind treasures. A teaching concealed as an intentional treasure appears directly in the mind of the tertön, that is, one who is a discoverer of the most profound teachings, in the form of sounds or letters. These sounds and letters may be found in texts, images, instruments, relics, artifacts, and medicines, temples, monuments, memorials, mountains, rivers, forests, even sky. So, Giant Step consociates, please look for me every now and again on the Jim Cohn home page at http://www.poetspath.com/.